Delayed milk ejection and reduced milk yield

Delayed milk ejection can affect milking efficiency, cow comfort and a dairy farm’s bottom line.

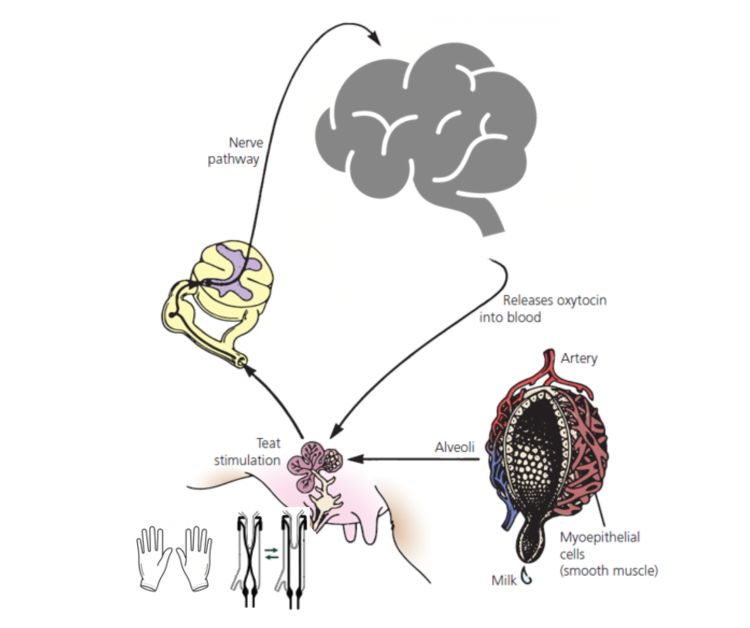

The letdown or milk ejection reflex is a process in which oxytocin is released from the pituitary gland of a dairy cow and travels through her bloodstream. When this hormone reaches the myoepithelial smooth muscle cells in the udder, it causes them to contract and release milk.

This process requires tactile stimulation of the teat. On dairy farms, this comes from fore stripping done by milkers or teat scrubbers. Because oxytocin travels through the bloodstream, the milk ejection reflex typically occurs between 30 seconds to 2 minutes after stimulation. When everything works well, the cow enters the milking parlor, her teats are stimulated and cleaned, the milking unit is attached, and she produces a consistent flow of milk for 3 to 8 minutes. The milking unit detaches, her teats are disinfected, and she leaves the parlor.

What is delayed milk ejection?

Delayed milk ejection (DME) is an interruption or delay in milk flow after the unit is attached. Normally, milk begins flowing within 30 seconds, and delayed milk ejection is a delay of over 30 seconds before milk flow. There are several causes and risk factors for delayed milk ejection.

Inadequate stimulation: On many farms, fewer workers are moving more cows through the milking parlor than in the past. This can mean workers are not spending the 10 to 15 seconds of hands-on time per cow to adequately stimulate the milk ejection reflex.

Insufficient lag time: Rushed employees may also provide an insufficient lag time, or the time between stimulation and milking unit attachment.

Stage in lactation: Animals earlier in lactation typically have more milk in their udders and a higher intramammary pressure than animals later in lactation. Similarly, animals milked twice a day have more time for the udder to fill and increased intramammary pressure compared to those milked three times per day.

Fear and stress: Fear and stress disrupt the production of oxytocin. Unfamiliar environments, increased handling and new routines can all contribute to stress, especially early in the fresh period for first lactation cows.

Other factors: Past research has observed a potential relationship between lameness and milk production. Lameness is associated with increased inflammation, which in turn may negatively influence milk flow dynamics though impairment of the milk ejection reflex.

Finally, there is a positive association between herd size and DME, perhaps due to a decrease in hands-on time spent on each cow.

How is delayed milk ejection detected and measured?

Understanding that delayed milk ejection is problematic is only one part of the issue. There are a few ways to measure DME on commercial dairy farms.

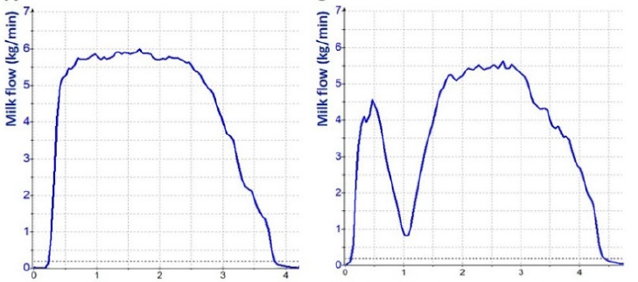

A Lactocorder is a portable milk flow meter that measures the milk leaving a cow in kilograms per minute. In Figure 2, normal milk flow is shown in the left graph. Delayed milk ejection is pictured in the right graph. Milk flow initially increases as in the normal flow graph but then decreases from 30 seconds to 1 minute after unit attachment.

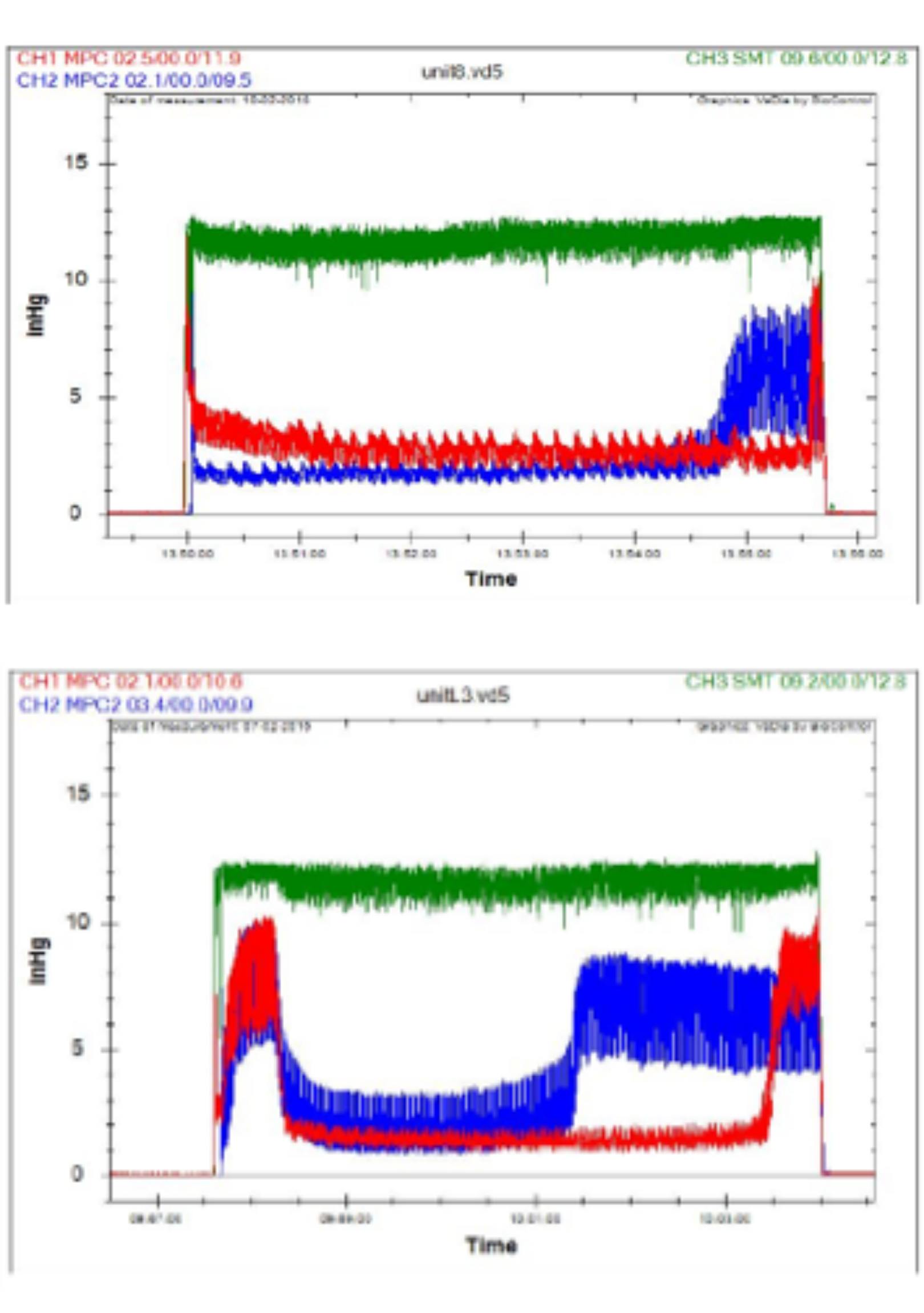

VaDia devices monitor vacuum levels as a proxy for milk flow. When there is low or no milk flow, the teat barrel gets thinner. This leads to a poor fit between the teat and the liner of the milking unit, allowing higher vacuum pressure to reach the mouth piece chamber. Therefore, a VaDia attached to a cow with bimodal milk flow will show a higher initial pressure when milk is not flowing.

In Figure 4, the top graph shows normal milk flow where pressure on the Y-axis remains consistent over milking time on the X-axis. In the bottom graph, the higher initial pressure graphed in red indicates that milk is not flowing.

Finally, milk flow can be visually assessed by observing milk flow into the cluster after unit attachment. However, this can be time consuming and impractical on larger dairy farms.

Why is delayed milk ejection a problem?

Delayed milk ejection isn’t just a minor annoyance, it can impact the cow, the workers, parlor efficiency, and even a farm’s profitability.

Teat and udder health: During low milk flow, the milking vacuum can penetrate the teat and mammary gland and collapse the teat, allowing the cups to “climb up” and interfere with blood flow. When teats lose contact with the liner, this leads to an increase in the mouthpiece chamber vacuum which induces teat congestion.

Animal welfare: Some cows shift weight, kick or attempt to remove the cluster during delayed milk ejection episodes when low milk flow exposes the teat to high vacuum levels. These behaviors typically indicate discomfort in cows.

Parlor efficiency: Cows with delayed milk ejection often require increased machine-on time, decreasing parlor throughput. Recent research confirms that machine-on time is longer without adequate premilking stimulation and attributes this to a higher percentage of delayed milk ejection compared to milking with adequate stimulation.

Milking technician safety and compliance: Undesired behaviors such as kicking can cause worker injury and early cluster removals, making more work for farm employees. Milkers have to clean and reattach the units. These tasks can put additional pressure on an already tight schedule.

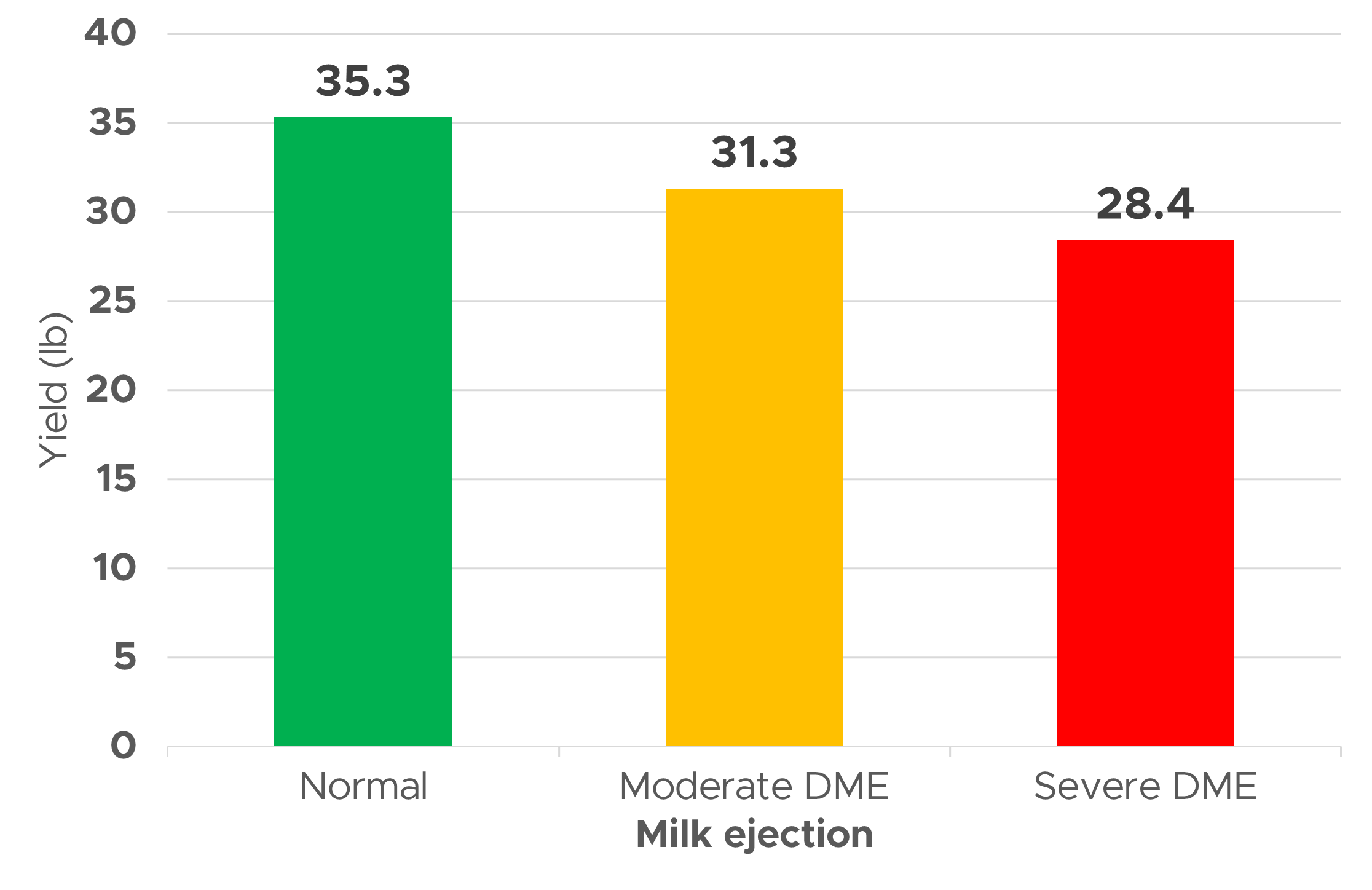

Milk production: Perhaps the most significant impact of delayed milk ejection is its association with lower milk yield. Past research by Michigan State University professor Ronald Erskine showed that cows with moderate (milk flow in 30 to 59 seconds) or severe (milk flow in over 60 seconds) delayed milk ejection produced 4 or 6.8 pounds less milk respectively than cows with no delayed milk ejection.

This gives rise to the phrase, “One minute delay, seven pounds tossed away!”

Cows experience delayed milk ejection at variable rates. Over a 10-day study period that observed 30 milkings per cow, many cows had no or a very low percentage of delayed milk ejection milkings, while other cows had rates of delayed milk ejection over 90%. As the percentage of delayed milk ejection events increased, the total milk yield decreased. This effect was consistent when accounting for parity, lactation stage and farm.

Therefore, cows with even occasional delayed milk ejection may contribute to lower milk yields in the herd. Each 1% increase in delayed milk ejection percentage over the 10-day observation period resulted in a reduction of milk yield by almost 1.2 pounds.

While it may be easiest to spot the cows that consistently have delayed milk ejection, cows that occasionally exhibit this can be contributing to lower milk yield on a farm as well.

What can I do?

Does delayed milk ejection affect your farm’s bottom line? Farms should first identify if delayed milk ejection is occurring on their farms using one of the methods described earlier. If delayed milk ejection is occurring, then look for potential causes. Are your milkers adequately trained to provide enough stimulation and sufficient prep lag time? Are cows handled calmly in a consistent environment? Are lame cows identified and treated in a timely manner?

Not sure where to start? The dairy educators at Michigan State University Extension can help!

Print

Print Email

Email